Lately I have got a bit hooked on buying vintage Parker fountain pens on eBay. I have been fortunate in finding some classic pens with gold nibs and plenty of life left in them, at attractive prices.

The latest to arrive was a Parker 61 Flighter. This was an impulse buy after receiving one of eBay’s thoughtful emails, that an auction of a pen I had viewed, was soon to end and inviting me to make my bid. By the time I read the email, the auction had barely 60 seconds left to go. I made a quick decision to bid and watched nervously as the final seconds ticked down. I did not have long to wait. The outcome was that three people had bid in the final minute. By a stroke of luck, my bid of £31.36 had won, by just 85p.

The pen arrived this morning. Although I have enjoyed Parker pens since the 1970’s, I had not owned a Parker 61 before. I recall being very enamoured with Parker’s Flighter pens, as a ten year old boy.

First impressions were good. The brushed stainless steel finish feels smooth and luxurious. The slip cap pulls off silently and easily yet feels secure enough when on. The pen is more sleek and tapered than my Parker 51, and slightly shorter overall, yet the grip section is about 1cm longer. The Parker 61 has a distinctive inlaid arrow on the section, introduced to help people know which way the tiny nib was facing, although these are known to fall off.

The Parker 61 was first introduced in the USA in 1956 but not in England until the early 1960’s. The early models featured an innovative new capillary filling system. This was part of the quest for a convenient method of refilling a fountain pen without the mess. This new system consisted of a cylinder coated in Teflon, a non-stick finish. To fill the pen, the user had simply to unscrew the barrel, place the pen, nib up, in a bottle of ink, and wait about 30 seconds for the cylinder to fill itself by capillary action. Then the pen could be lifted from the bottle and, in theory at least, ink would not adhere to the Teflon coating. The barrel could be screwed back on without a need to clean the cylinder.

In practice the Teflon would flake off eventually and some cleaning was necessary. It seems that the system was not as popular as hoped. Also, there was a tendency for the cylinder to get clogged up, if the pen was not cleaned out from time to time. Before long the system was dropped and instead, later versions used Parker’s new cartridges or else a detachable aerometric-style cartridge-converter.

My model has the cartridge-converter. I do not know the date of it. It was made in England, which puts it before the closure of the Parker Pen factory in Newhaven in around 2011. But I read on Tony Fischier’s site, parkerpens.net that the Parker 61 range was discontinued in 1983 and so my pen is at least 40 years old. It does not have the “Quality Pen” date code on the cap, introduced in 1980 and so I can narrow the date down to 1960’s or 1970’s. I suspect that there are other clues to discover.

On its arrival, my pen still had traces of blue ink and I gave it an initial flush in water, using the converter. On squeezing the converter, a healthy stream of air bubbles was emitted from the nib, an encouraging sign.

Then as I removed the converter to wash out the section, I noticed that the connector was loose and rotating. I carefully unscrewed this, whereupon I could take out the nib, feed and ink collector, separate them and give them a clean.

I was careful not to lose any small parts. In my excitement, and after cleaning and photographing the pieces, I forgot the sequence for reassembly and watched an informative YouTube video from Grandmia Pens, which set me right. Steff advises against unscrewing the shell in the Parker 61s, as they are prone to cracking and shrinkage. It is not advisable to apply heat to them to soften the adhesive, (as you might with a Parker 51) for this reason.

Although the pen in his video was the capillary filler version, the principles are largely the same, as follows:

- first find the channel in the the ink collector. This should be aligned with the nib;

- insert the nib carefully into the collector, pushing it in as far as it will go.

- slide the black plastic feed into the ink collector from the back, all the way into the nib, which leaves a small part of the nib protruding beyond the feed;

- insert the nib, feed and ink collector into the shell, or section; notches will align them correctly;

- preferably, apply a little silicone grease to the threads, before screwing the connector inside the shell with the end of the feed passing through the hole in the connector;

- push the converter back onto the section.

This all went very smoothly. I was pleased that the connector was not glued, enabling me to take the pen apart safely and clean the components. For those with the capillary version, there will be a retaining washer gripping the cylinder on the connector. This slides forward onto the ink collector, for the cylinder to be removed for cleaning, then later slides back over the end of the cylinder again to secure it. Note also that the plastic feed is much longer in the capillary fill version.

On examining the nib, there was no date code on it. The gold cleaned up very easily. The nib appeared very slightly bent and the tine gap was rather wide, such that the pen was likely to be a gusher. Rather rashly, I squeezed the sides of the nib together, to narrow the tine gap a little, which had the desired effect. After this it was necessary to realign the tines, for smooth writing.

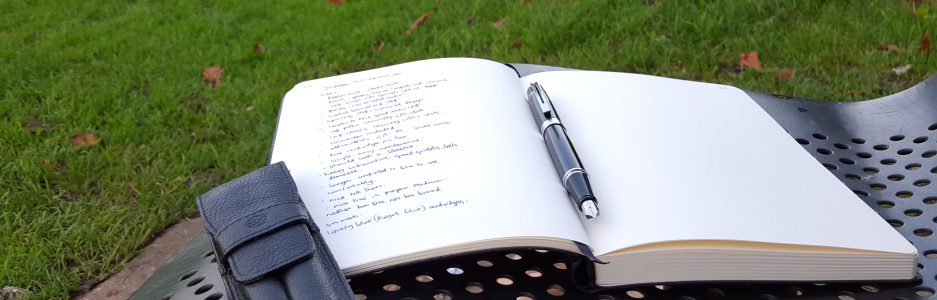

At the end of this exercise, I filled the pen with Waterman Serenity Blue, and tried writing on a Stalogy A5 notebook. Success! The pen writes very nicely. Whilst the generous blob of tipping suggested a Broad nib, the line is closer to a Medium.

I have much enjoyed my first day with this pen, tinkering, cleaning, photographing and writing with it. For the pleasure it gave me today, I have already got my money’s worth and so every new day with my Parker 61 will be a bonus.