Looking back at the fountain pens which have been particularly significant for me, there is probably none more so than the basic Sheaffer No Nonsense. Certainly, these got the heaviest usage. These are the pens that I used as a law student at Bristol Polytechnic (as it was then called, but now the University of the West of England), from 1977-80.

I would buy these from a local WH Smiths. They were sold on hanging card blister packs. I cannot recall the price back then but it might have been around £7.00. There were a few different nib options including Fine, Medium and Italic but I mostly went for the Medium nib. They took Sheaffer Skrip cartridges. A Sheaffer converter could be used, of the push button or press bar type, if you had one, but the cartridges were easier, to refill mid lecture. Just unscrew the barrel, remove the empty cartridge, drop a new one into the barrel and then screw the section back on; the pen did the rest.

Looking back on my first term at Bristol, the amount of information that we were expected to take in, assimilate and learn, was daunting and stressful. Typically a college day included two hours of lectures, always in the same lecture theatre with its banked rows of orange, folding seats, each with a small, fold-out tray from the arm rest, rather like the aisle seats in a passenger plane. These were barely big enough to support an A4 pad of notepaper, let alone the printed handouts of course material to refer to. Being left handed, I remember the dilemmas of whether to take notes by annotating the printed handouts, (which were of varying degrees of detail) or by writing on my A4 pad and, more fundamentally, whether to write in lefty-underwriter style (with my elbow tucked in) or my faster, neater more usual, lefty-overwriter style, which meant rotating the notepad 90 degrees anticlockwise.

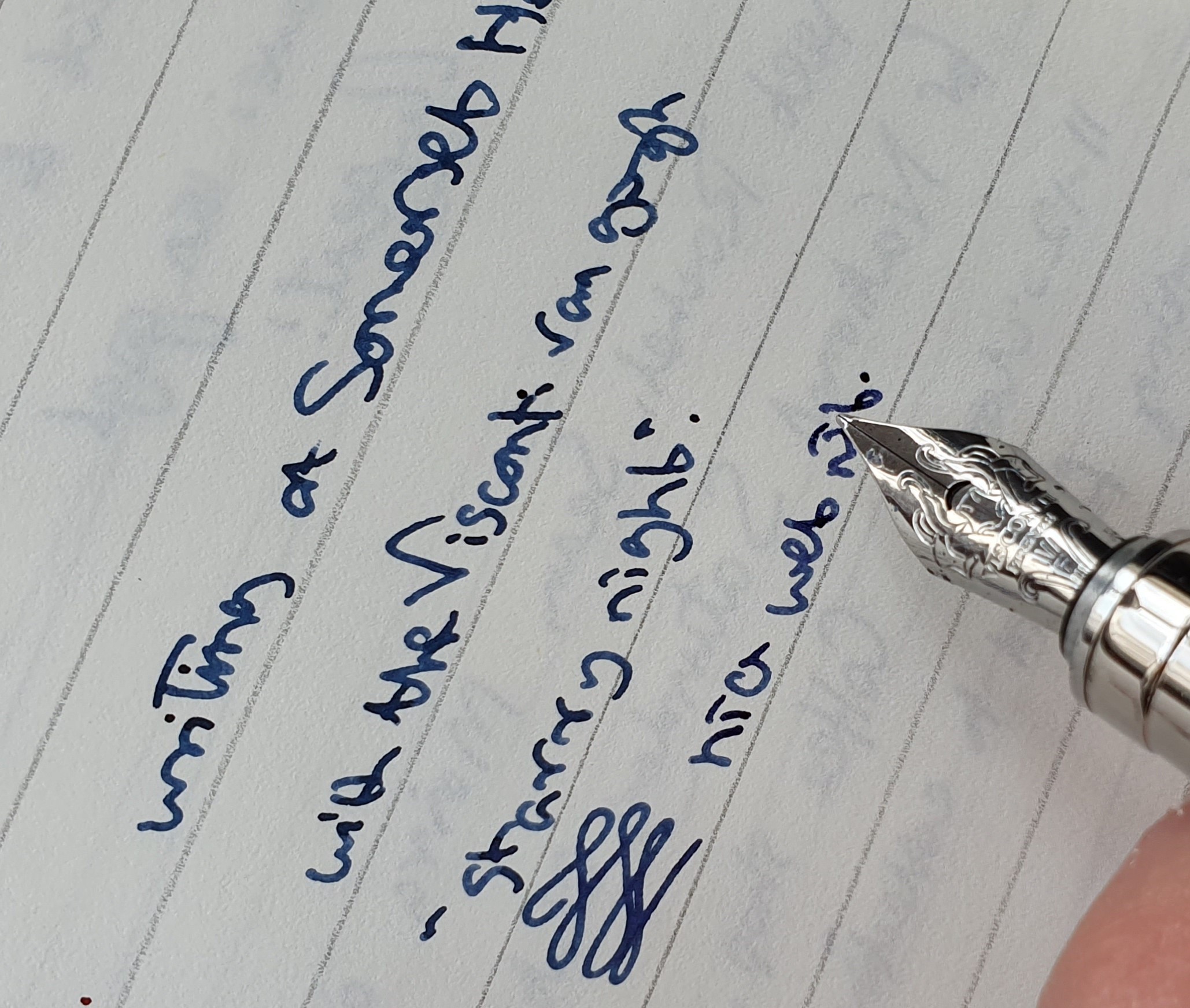

I decided on the latter, overwriter style on A4 paper and also settled on black ink. In a typical lecture, I would write six pages full of notes in an hour. A reliable and comfortable pen was essential. The No Nonsense pens, with their firm, steel nibs, were well suited to this regime. The feeds were plastic although looking at them now, I have one which is of a different shape and might be ebonite. Some of the fins have broken off.

Over the months, the nibs would wear down, so that the rounded pellet of tipping material would develop a circular, flat foot. By then, the writing experience would be super smooth for my writing angle but if you strayed away from this sweet spot, you would encounter a sharpened edge which would be scratchy. Eventually, when the nib was worn and getting too scratchy and when I fancied a change, I would replace the pen. Well, I say “replace” but I just bought a new one and never disposed of the old ones. I still have them all.

Aside from using the pens for lectures, study notes and essays, it was also my practice to write up my diary each night, using small, page-a-day diaries from Boots. These were chunky little volumes, about the size of a pack of playing cards, with a page of plain, thin, fountain pen-friendly paper for each day. I would use reverse writing, (writing with the opposite side of the nib) to get an extra fine line and would, with very tiny writing, manage about 28 lines to a page. Back then I did not know that this was called “reverse writing”, SBRE Brown being not yet born.

I do not think I had a strong magnifying glass at that time, let alone the ability to take macro photos of pen nibs, and with a mobile phone! But looking now more closely at some of those No Nonsense nibs, there is wear on both sides of the nib so that the tip is almost like a sharp chisel.

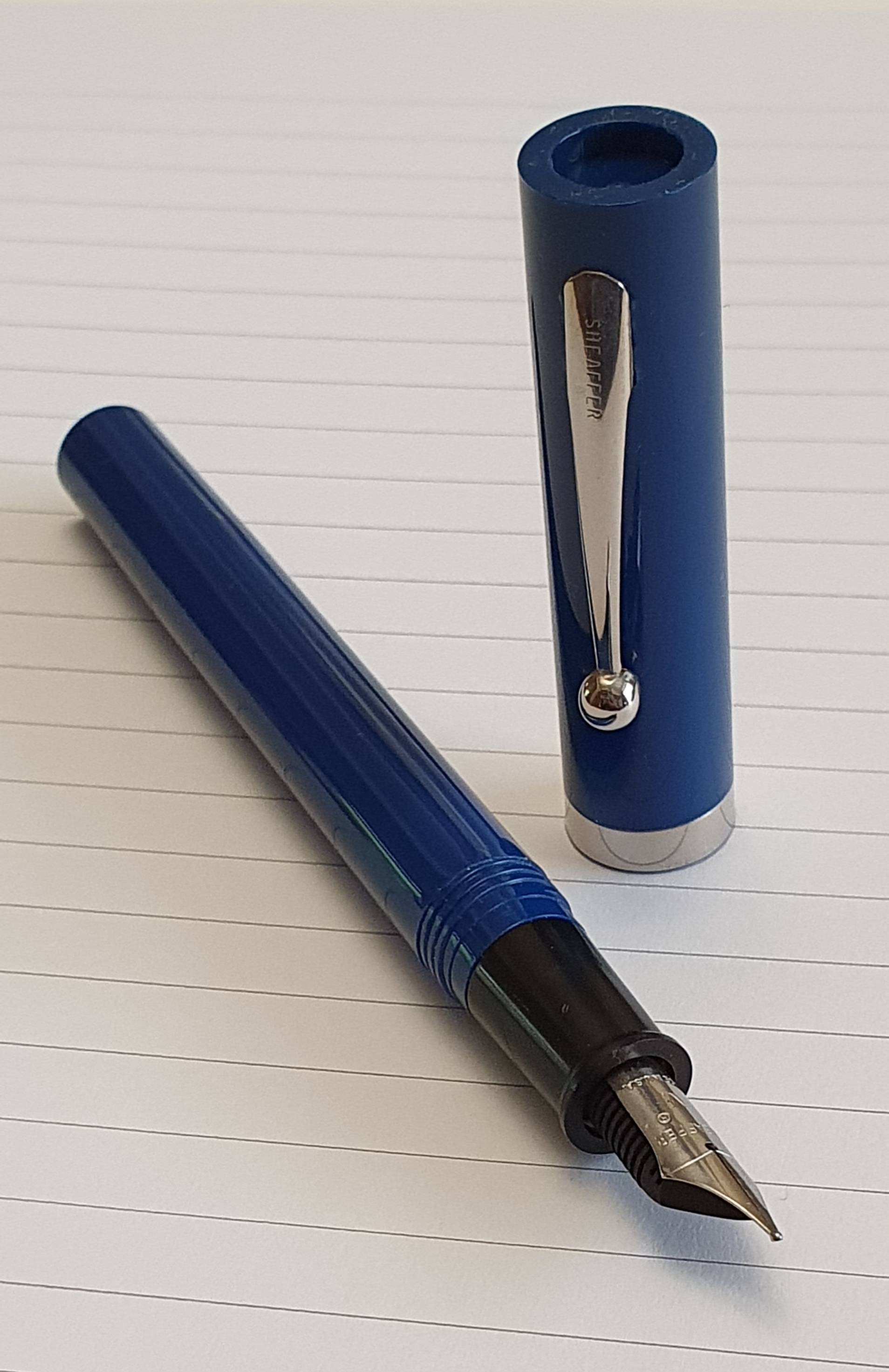

The Sheaffer No Nonsense was available in various colours but I tended to buy blue, black or white. I also found some metal bodied versions, supposedly superior and bought a couple of these although I actually preferred the normal, plastic ones.

Rooting through a tin of old, long-since retired pens, I assembled my No Nonsense pens for a group photo:

And here, in a never-before-seen-together group shot, are the nibs that got me through college:

The pens, as the name suggests, were no frills, basic, workhorse tools. They were of a good size, 121mm opened and 151mm posted. Being plastic they were very light, but solid. The caps featured a sturdy metal pocket clip with a round ball at the end which would serve very well although I carried mine in a pencil case. The brand Sheaffer was imprinted in the pocket clip. There was no Sheaffer white dot, for reasons unknown to me as I do not think that this would have added much to the cost. There was a chrome cap band, devoid of any text. The cap unscrewed on plastic threads, in one full rotation.

The steel nibs were imprinted with the name Sheaffer, the registered trade mark circled R, the nib grade and Made in USA. I suppose that this meant in Fort Madison, Iowa which I understand closed in 2008. There is a Sheaffer Pen Museum there now, with displays of their many ranges of fountain pens, desk pen sets, advertising posters and memorabilia as well as some fascinating old machines from the former factory and a gift shop. I have not been but enjoyed an amateur video of a trip to the museum on YouTube.

The No Nonsense pens are still produced as calligraphy sets although last time I bought one it was disappointingly plasticky, with a snap cap, soft grip section and a huge open ink window in the barrel.

Some years after college, I bought myself a Sheaffer Connaisseur, which seemed to be an upmarket version of the No Nonsense with an 18k gold nib. It sounds good on paper but I never really took to it for some reason.

Not long ago I inked up one of my No Nonsense pens, the blue plastic one with a super-smooth nib. It is still very usable and still remembers my writing angle. But I think it has deserved its retirement now.